I’m going to tell you a secret: editing is largely subjective and there are fewer rules than you’ve been led to believe. I mean, there are rules and guidelines, but how to apply them is subjective. You can give five editors the same passage, and you’ll end up with five different final versions.

And that’s okay.

Because here’s another secret: writing a novel is really about reading.

I’m going to repeat that because it’s so important.

Writing a novel is about reading.

How good or unique or clever your story is won’t matter if you have no one to read it, if you have no one who wants to read it. As the author, you want your reader to be engaged and interested in your story so they want to find out what happens next.

And that’s where the rules and guidelines come into play. These rules help readers know what to expect. When a reader sees a quotation mark, they know a character is speaking. When a reader sees an apostrophe, they know it’s for a conjunction or to show possession. Knowing when and how to disregard the rules is as important as just knowing them—if there’s a period after only one word (an incomplete sentence), the reader will understand it’s an important word.

And that brings me back to the first secret—editing is largely subjective. The changes I make in an author’s prose are not necessarily the same changes another editor would make, because editing is a collaborative process. An author writes a sentence, the editor makes a suggestion about how to improve the sentence, and the author decides whether the suggestion helps or hinders the message they’re trying to convey.

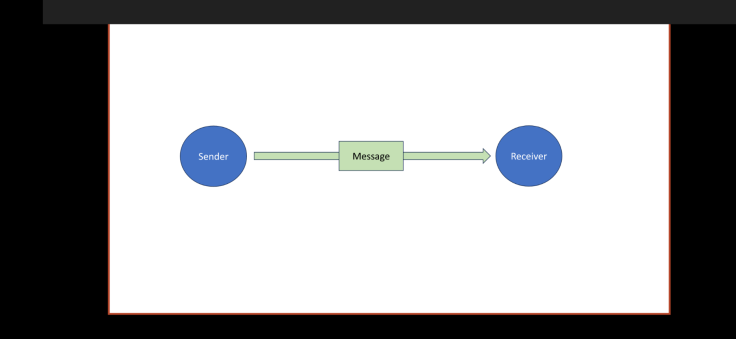

Way, way back a long time ago when I was in college, we discussed a basic communication model in several classes (which made sense—I majored in mass communication). The basic idea is to have a sender, a receiver, and a message. The sender creates a message and sends it to the receiver, who interprets the message. In an ideal world, everybody is on the same page.

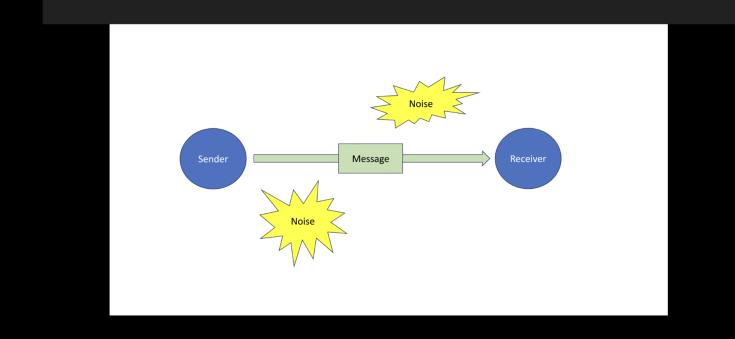

The problem comes from not living in an ideal world. In the real world, each person comes to the message with their own knowledge and expectations—what we call noise here—and the message can be misinterpreted.

Sometimes it’s because the sender assumes knowledge the receiver doesn’t have; sometimes it’s because the receiver has a weird bit of trivia the sender doesn’t have. The actual reason for the misinterpretation doesn’t matter. The problem is that there’s a misinterpretation at all.

Which is why you hire an editor: to get rid of the noise—or as much noise as possible. Each editor is making sure the reader interprets the message the author is trying to send. It’s not just correcting commas and homonyms. I regularly ask authors “Does this sentence mean XX or YY?” or “Who is speaking here?” And I ask those things because I want your readers to love your story as much as you do. I want them to feel what your characters feel, to know what your characters know.

When I’m working with a manuscript, I’m guided by this reader experience. I want to make sure your readers have the experience you want them to have, which means preserving your voice through every stage of the editing process. And that brings us back to editing as a subjective thing. If any editor is changing your message too much, then that editor isn’t the right fit for you (though they may be for someone else).

If you have any questions about this or anything else you’ve read here, please feel free to reach out to me at any time.