Thousands of editors have tried to explain the difference between the levels of editing. I’ve even done it myself, but I’ve long wanted to show the differences between line editing, copyediting, and proofreading. (Developmental editing is a completely different beast—you can learn a little about it in this explanation of manuscript evaluations.) I asked ChatGPT to write a story for me. It’s one of the few legitimate uses of generative AI—I needed it to be poorly written and didn’t want to violate the privacy of any of the authors I work with.

In the following pictures, you’ll see marked-up versions of the story for each level of editing. At the end of this post, you can find the original story next to the fully edited story.

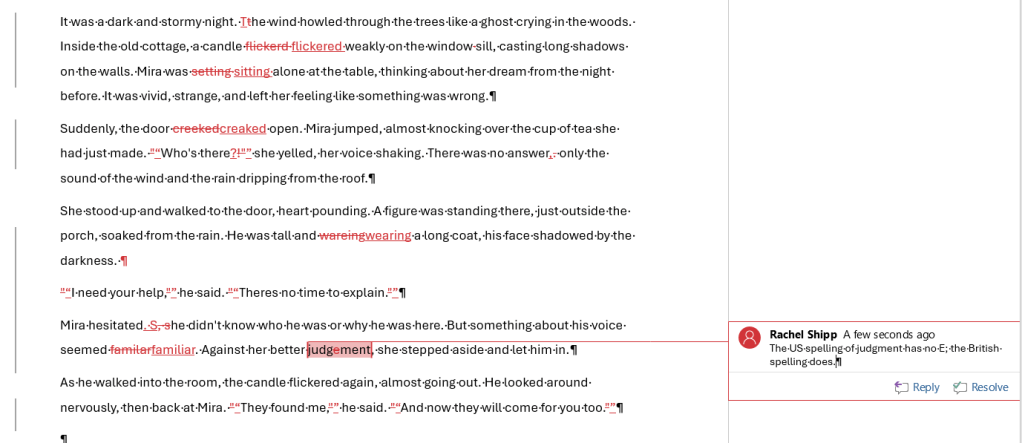

First up is proofreading. As you can see, the changes are very simple and focus mostly on spelling and punctuation corrections. Proofreading doesn’t fix your prose; it only makes sure everything is correct and follows the style sheet.

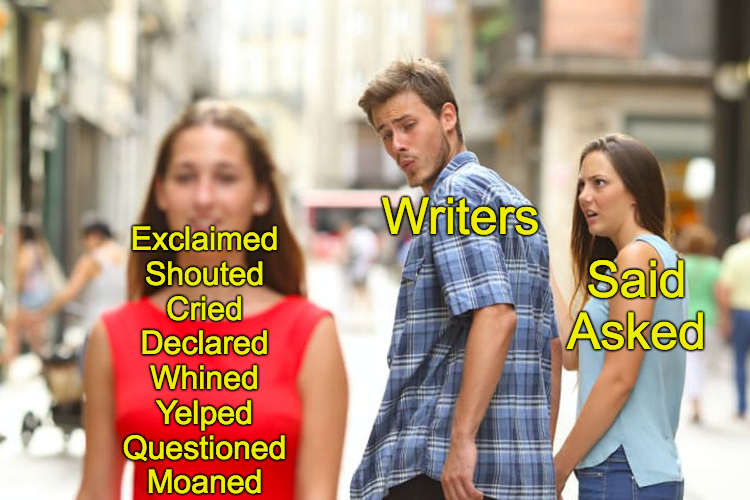

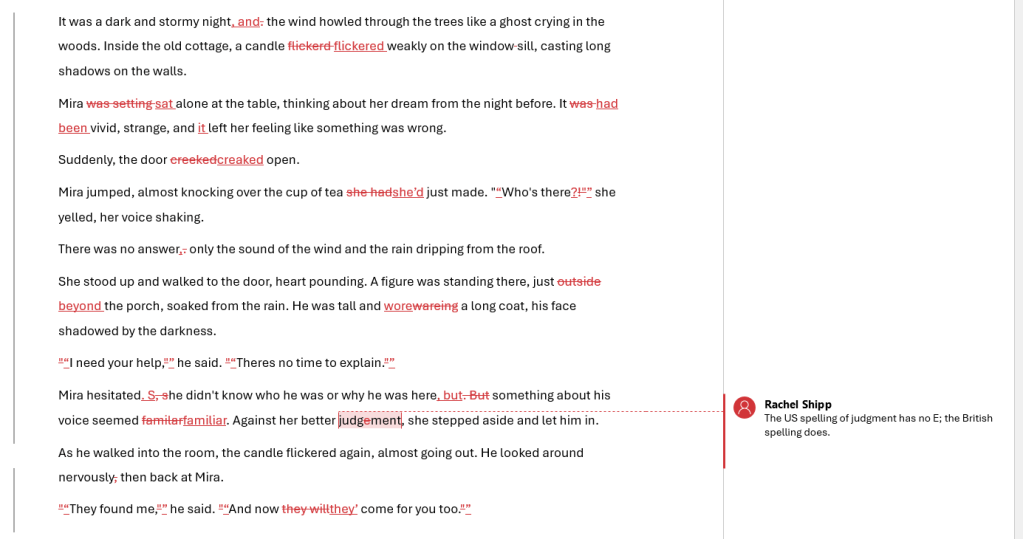

Next is copyediting. You can see the same changes I made in the proofreading round, but I’ve also changed some of the words for a more active and exciting tone. In a longer text, copyediting would include making sure things are consistent throughout the manuscript—are your main character’s eyes gray, grey, or blue? Is the pirate ship called Titan’s End or Titans’ End?

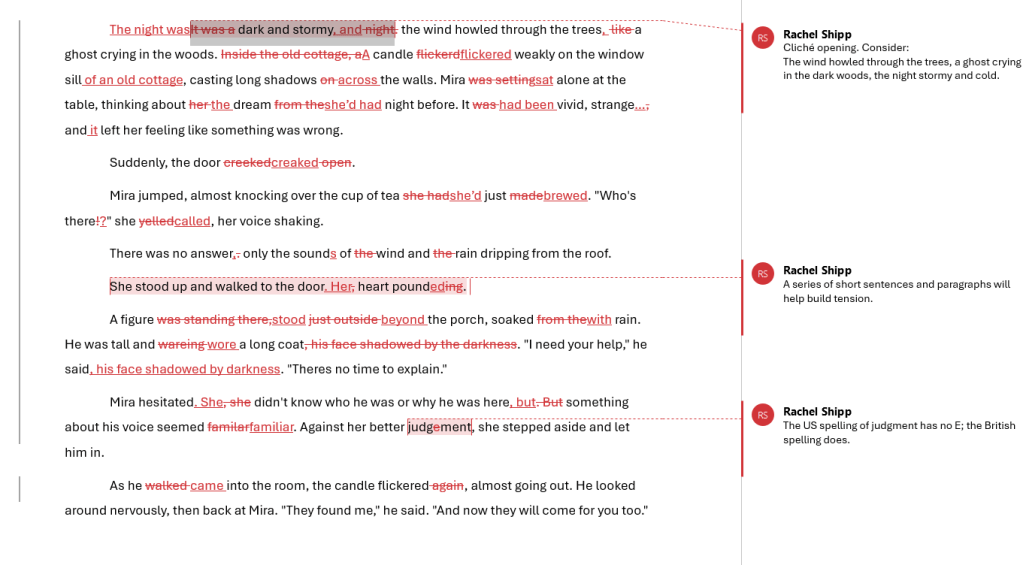

Finally, this is my line edit of the story. Here, you can see where I’ve focused on the syntax and mood. Along with changing the text, I’ve explained to the imaginary author how to add tension and avoid clichés. I also do a decent amount of fact checking in my line edits, but not every editor does.

The lines between each of these levels are very blurry. I stopped offering separate services because I couldn’t stop myself from line editing every manuscript, no matter what service I’d been contracted for. As such, I do a little bit of them all between two passes.

If you choose to contract different editors for each step, start with the line editor and work backward—there’s no point in proofreading text that will have large changes made to it.

Click here to learn more about my services. And as always, please contact me with any questions about anything you read on my website.

For the sake of comparison, here is the original story as written by ChapGPT.

And here’s the story after all my editing.